Canada’s residential school system for Indigenous youngsters had one purpose: to "fix" these children by erasing all traces of their heritage. Much like American Indian boarding schools (as well as similar systems in other countries), Canada’s default approach to “handling” Indigenous youth was inhumane, cruel, and led to deaths and abuse of the forced attendees. The horror perpetrated at these locations doesn’t just vanish once the schools close their doors. Trauma revibrates well into the present. Systemically ingrained dehumanization of Indigenous people still informs Western society today. A long-lasting institution declared “a cultural genocide” doesn’t just vanish.

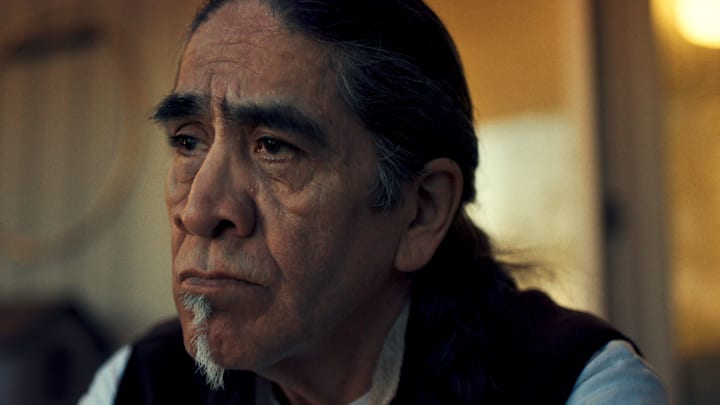

The documentary Sugarcane follows a collection of perspectives from the Williams Lake First Nation grappling with the lasting after-effects of these schools. One story concerns Sugarcane director Julian Brave NoiseCat (Emily Kassie also directs) wringing answers about the past from his father, Ed, who attended one of these schools. Other segments chronicle people scouring for bodies and unmarked graves where these schools once stood. Then there's Rick, a man deeply immersed still in the Catholic faith (many of these schools were also Catholic institutions). Here is a fellow whose traumatic past torments him daily. However, he's also dedicated his life to the theological backdrop of that adolescent anguish. Rick’s life epitomizes the various complicated figures dominating Sugarcane.

Occasionally interrupting newly filmed modern-day footage in Sugarcane are monochromatic excerpts from the 1962 documentary The Eyes of Children. These clips depict “tranquil” footage of Indigenous youngsters at these Catholic schools. It’s a facetious warping of reality passed off as reality to white viewers. These segments arrive with no warning. When they do appear, they often flicker on screen with minimal or no accompanying audio. There’s a haunting sparseness to these images, an extension of how suppressed Indigenous lives were in these institutions.

The way these clips emerge in Sugarcane often also reflects the past intertwining with the present. NoiseCat and Kassie’s best demonstration is a sequence depicting a contemplative Rick playing “Silent Night” on the radio. Suddenly, the feature shifts into archival footage of Christmas morning at one of those horrific schools. “Silent Night” keeps on playing in this flashback, creating a sonic bridge between two points in time. There’s no ham-fisted narration or on-screen text to reinforce the unity between these two sequences.

The confidently sparse transition between past and present in this striking Sugarcane sequence leaves things fascinatingly ambiguous. Is this archival footage a symbol of Rick’s thoughts? Is “Silent Night” triggering overwhelming memories of his past? Does emphasizing that song across these time periods reflect the lasting effect of religious trauma? So many fascinating interpretations emerge in this one sequence which crystallizes how well Sugarcane incorporates footage from the past. The specific placement of those segments brings us closer to modern-day human beings and their psychological torment.

A deeply humanistic approach informs that and other key qualities of Sugarcane, including its observational style of filmmaking. This documentary isn't interested in polished interview segments or narration holding the viewer’s hand through Indigenous Canadian history. Rather than force ordinary people to adhere to standard documentary filmmaking, NoiseCat and Kassie bring the camera Sugarcane’s central subjects. Conversations with people like Rick occur while they load old trinkets into a truck. Meanwhile, an off-hand exchange between NoiseCat and his grandma at a local community event is filmed from afar. Subtitles clarify their dialogue amidst the surrounding noise.

Far more often than not, individuals on-screen never acknowledge they’re being filmed. This accentuates the perception that we’re witnessing truly authentic and raw slices of life. Sugarcane is not creating controlled recreations of existence. Instead, the feature bears witness to reality as it unfolds.

This style of filmmaking also allows viewers to witness lighter moments in the lives of on-screen figures. Most notably, NoiseCat and his father’s brief mid-movie road trip involves bursts of levity. They sing along to tunes like Neil Young's "Old Man" while NoiseCat makes a wet T-shirt contest joke about Ed. These don’t undercut or take away from the raw, severe material Sugarcane is grappling with. Instead, they frame Sugarcane's central subjects as fully-dimensional people. Folks grappling with trauma aren’t just miserable 24/7. The psychological after-effects of trauma intrude even on seemingly idyllic days.

Understanding those nuances informs the mundane bursts of joy filling various Sugarcane scenes, like Rick’s excitement at showing his wife (through a Zoom call) various trinkets he picked up in Venice, Italy. In their own way, these glimpses at more joyful experiences are also a gigantic middle finger to the entire ethos of those residential schools. These institutions only existed to torment indigenous people. These souls were seen as so disposable that Indigenous kids could be murdered and nobody in power would make a peep. Yet, here are surviving students like Ed and Rick, still alive and capable of feeling such vivid exultation. Sometimes, survival itself is a form of rebellion. So too is absorbing fleeting ebullience. Sugarcane’s quiet dedication to chronicling nuanced portraits of Indigenous existence is one of its greatest traits.

Sugarcane is not a movie about resolution or finding easy answers. By the end, the search for unmarked graves continues on. Internet trolls try their hardest to shift the blame for this genocide onto the Sugarcane residents. Prolific figures Pope Francis only offer surface-level condolences and acknowledgment of these atrocities. They don't engage in more drastic and meaningful responses to the past. “Apologies are everywhere,” Rich observes while in Italy, “but nothing ever changes.” NoiseCat and Kassie brutally frame the reality of how privileged classes handle the aftermath of genocide: in a tidy fashion reducing horrors of the past to the actions of “a few bad apples”. Onlookers and descendants of perpetrators create a barrier between themselves and the anguish folks like Ed and Rick cannot opt out of.

Sugarcane’s reserved observational filming style hammers home how this horrifying reality manifests in such mundane ways. However, that filmmaking approach also humanizes Indigenous lives that those schools were meant to eradicate. A perfect example is NoiseCat and Kassie letting raw footage of one survivor being encouraged to exhibit emotional vulnerability without ham-fisted accompanying music or narration. The focus remains on her story and emotions. Intrusive elements designed to indicate how the audience is feeling right now are M.IA. “It’s okay to cry,” a woman onlooker tells this survivor. “Let’s just hold each other.” Deftly portraying this beautiful exchange epitomizes the specialness of Sugarcane’s richly human craft.