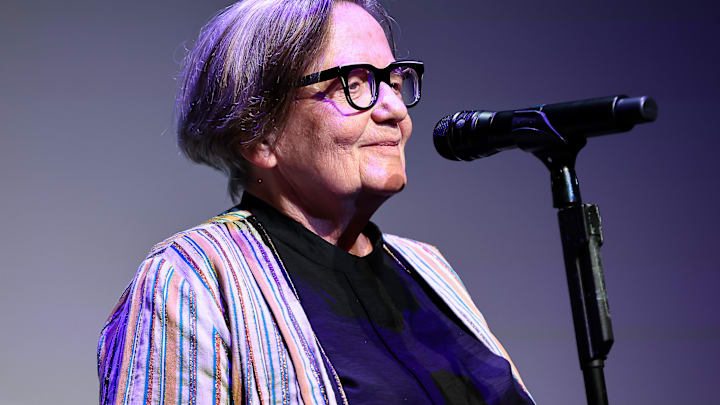

Director Agnieszka Holland uses cinema to bear witness to the unthinkable. In the real world, historical atrocities like the Armenian Genocide, the oppression of Palestinians, and other horrors are denied. The persecution and extermination of the marginalized is an “opinion” to be debated in the public square. Holland's works put events on the silver screen complete with the complicated human beings inhabiting those horrifying circumstances. "I think it’s time for the movies to take a stand," Holland told Docu Days UA in March 2021. There she was speaking about her perception that modern Polish cinema lacked political verve. However, might as well have been talking about her entire approach to filmmaking. Cinema is not just escapism for Holland. It’s about planting your feet against fascism, both past and present.

Holland's cinematic fixations are exemplified once again in her latest directorial effort, Green Border. Past Holland features firmly occupied the past. They chronicled events like the Holocaust or existence in 1930s Soviet Russia. Green Border, meanwhile, inhabits an era of cell phones, COVID mask protocols, and discernibly modern automobiles. Taking place in the 2020s allows Green Border to chronicle multiple perspectives on the Belarus–European Union border crisis.

The first of the perspectives explored by screenwriters Holland, Maciej Pisuk, and Gabriela Łazarkiewicz-Sieczko takes place on an airplane. Hope courses inside Bashir (Jalal Altawil) and his family on their flight. Once they land, they hope to do some brief traveling and finally start a safer life in the European Union. There’s an intentional naturalism to these early scenes of tranquility. Holland deftly guides us to the different personalities of Bashir’s various family members (which includes two young kids and an elderly grandpa) as they interact on the plane. Youngsters are on their phones. Certain members of the family want to sit closer to the window.

Most importantly, as Bashir’s family loads up into a car taking them to their destination, a pair of strangers ask for a ride. They’re going to the same place, after all. For the rest of Green Border, audiences can't escape realistic depictions of strangers suffering dehumanizing rhetoric. Police officers and border patrol guards are all told to approach anyone who is “different” as an enemy hellbent on destroying Poland. Bashir and his family, meanwhile, offer to help these strangers with their automobile. Green Border begins its grueling runtime with acts of kindness and everyday reality from people often dehumanized as otherworldly caricatures.

This trip is cut abruptly short once Bashir’s family encounters Polish border guards. Our lead characters no longer get treated like human beings. They're merely viewed as political tools and terrorists in the making courtesy of Belarus. This perception informs the rampant cruelty exerted towards these immigrants by law enforcement officers and border patrol agents. This cruelty even extends to beating children and dumping water into the soil in front of dangerously thirsty prisoners. Holland and cinematographer Tomasz Naumiuk frame these atrocities in an incredibly frank fashion. Unlike Quo Vadis, Aida? or The Zone of Interest, Green Border is not a motion picture where horrific violence against the oppressed occurs off-screen. Truly chilling depictions of border guards reveling in abusing human beings fill entire frames. The camera rarely cuts away from these horrors.

In the case of Green Border, that feels like an appropriate approach to this story. For one thing, the “less-is-more” sensibilities of titles like the aforementioned Zone of Interest stemmed from subverting the visual norms of genocides frequently depicted on-screen. The Belarus–European Union border crisis and the anguish of immigrants in that specific crisis have far fewer cinematic precedents. Holland and company are establishing a visual language for putting these horrors on-screen rather than subverting a pre-existing language.

Meanwhile, Holland and cinematographer Tomasz Naumiuk avoid capturing this agony in a exploitative manner. Shallow visual and auditory tricks to emphasize the "importance" of this misery (such as slow-motion or a mournful angelic chorus accompanying physical violence against the innocent) never appear. Instead, there's a raw sparseness to their anguish. At times, this filmmaking process mimics the kind of photography one would see from cell phone footage of actual xenophobia. Holland and Naumiuk also employ a variety of types of camerawork to capture the struggles of Bashir and company. Elongated single-takes sometimes emerge, with extensive suffering captured by an unblinking camera. Handheld camerawork also appears to lend a frantic sensibility to intense moments. These and other qualities lend visual versatility to Green Border as a text. They ensure the feature avoids devolving into the visual banality plaguing other movies about atrocities like In the Land of Blood and Honey.

Holland and Maumiuk's black-and-white framing in Green Border is another deeply inspired visual decision. That color scheme is typically associated with momentous motion pictures chronicling past horrific atrocities. Green Border’s monochromatic color palette evokes that significance in a modern-day context. This terrific reinterpretation of a period piece visual motif also reinforces omnipresent danger for Bashir’s family and other immigrants. No specific bright colors code certain environments as “safe” for these individuals. Limited hues suffocate every realm in Green Border. So too are potentially fatal problems similarly inescapable for these characters. Meanwhile, the black-and-white cinematography lends real beauty to the various natural light sources beaming down on the forest where Green Border's immigrant characters are forced to dwell. These striking shots lend a sense of visual grandeur to lives often swept under the rug in society.

As Green Border keeps going, the story's scope expands to include characters like Julia (Maja Ostaszewska). This virtual psychologist feels she's much too busy to get involved in this immigrant crisis. Her story involves some of the most riveting sequences of Green Border, like a grippingly filmed car chase, a nighttime return to immigrant Ahmed (Aboubakr Bensaihi), and anything involving boisterous radical leftist Kasia (Malwina Buss). There is one downside to the extensive focus on her and other Polish citizens trying to help immigrants. That aspect of the scrip leaves one yearning for slightly more screentime on other supporting characters.

Julia and her fellow helpers get ooddles of screentime. Meanwhile, other seemingly pivotal immigrant characters in the feature, namely Bashir's wife Amina (Dalia Naous), barely get any discernible personality traits. This quibble's reinforced thanks to the compelling human behavior we witness. Viewers see Bashir and Grandfather’s (Mohamad Al Rashi) differing views on religion. The intriguing interior world of Polish border guard Jan (Tomasz Włosok) also occupies lots of screentime. A scene where he screams in his car in conflicted anguish, captured in a raw claustrophobic side-profile close-up, is deeply impactful. Most fascinating of all is the tragic Leila (Behi Djanati Atai). She’s a woman whose brother worked with the U.S. military in Kabul. She enters the European Union believing there is a system of justice in place. Simply telling violently cruel border guards “you can’t do this!” will surely make them stop.

Holland and company do not treat Leila as a naïve punching bag. She’s a tragic figure browbeaten by a world that should operate on some level of basic human decency. The clash between her worldview and the horrific realities she’s submerged in is transfixing. She’s a microcosm of how Green Border’s characters are such fascinatingly complex creations. It would’ve been divine to see a little more of Holland’s expansive cinematic canvas and thoughtful writing afforded to giving Amina and a handful of other immigrant figures some of that complexity and depth. Still, the figures that do get dimensions on-screen are truly riveting and resonate as deeply authentic creations. Their various nuances tragically accentuate the realism of the piece.

Watching these souls inhabit (or, in the case of figures like Jan, exact) relentlessly cruelty doesn’t and shouldn’t make for an easy watch. In the middle of all that anguish, though, Holland shows remarkable control of her craft. Just look at her precise implementation of Frédéric Vercheval's sparse score in the feature. Similarly, Holland and the other screenwriters deftly create a recurring thread on how women prop up fascist behavior and institutions. Women police officers torment Julia both out on the road and in a local police station. Jan’s training session as a border guard includes a lady psychologist standing by to serve as a willing punchline to the male speaker’s misogynistic jokes. One of Julia’s friends refuses to fully commit to helping immigrants. Her own economic survival is more important than fighting for freedom for all.

Anyone can be complicit in atrocities. That includes people oppressed in other ways in society. You can be marginalized in one sense and also complicit in reinforcing systemic inequality in another. Green Border effortlessly reflects that and countless other deeply uncomfortable aspects of reality. Agnieszka Holland’s superbly honed skills in historical injustices cinema perfectly fit this material. Once the credits begin rolling, Green Border will leave you infuriated and aching over ongoing atrocities. Don't avoid those emotions. Stew in them and the images that just flickered before your eyes. There's so much to process in a meticulously crafted piece of harrowing filmmaking like this.