Whether it’s Jon Favreau or Barry Jenkins sitting in the director’s chair, these modern Lion King movies suffer from the same problem: adhering to ultra-realistic digital animation. Mufasa: The Lion King helmer Jenkins is a master filmmaker responsible for some of the greatest movies of the 21st century, like Moonlight and If Beale Street Could Talk. Even he can’t evade this innate problem. Trying to wring compelling drama or powerful emotions out of vacant-eyed lions ripped straight out of reality doesn’t work. All these critters look the same. There’s little variety in their body language or physicality. It’s all so flat and unremarkable looking.

Mufasa yearns to be a grand addition to the Circle of Life. Occasionally, it flirts with being heartwarming. Mostly, like the abhorrent high-frame rate imagery of Avatar: The Way of Water or the most repulsive examples of digital de-aging (hi, The Adam Project!), Mufasa reflects “cutting-edge” tech undercutting a movie.

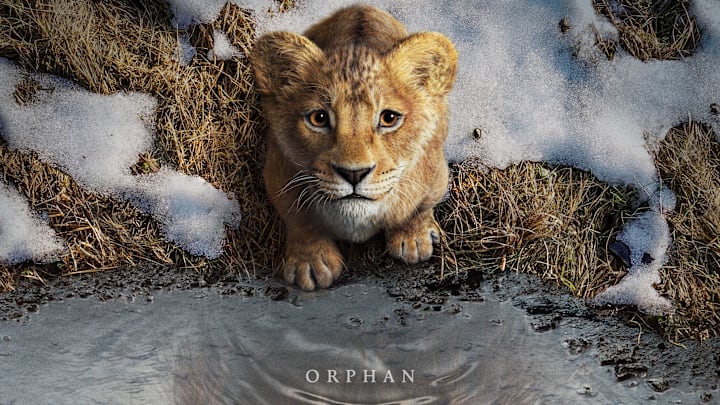

Like The Godfather: Part II or Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again, Mufasa is a sequel that features flashbacks to the formative years of the protagonist’s most important parent. In this case, Simba’s dad gets showcased through a story Rafiki (John Kani) imparts to Simba and Nala’s daughter, Kiara. Back in the day, Mufasa (Aaron Pierre) was not a guy who spoke in the beautiful voice of James Earl Jones imparting wisdom. He was just a lion cub washed away from his family, struggling to find a home. Eventually, he stumbled onto Taka (Kelvin Harrison Jr.), the prince of a royal lion bloodline. This youngster “always wanted a brother” (to quote Mufasa’s best song) and once his father reluctantly adopts Mufasa, he gets his wish.

Once these siblings grow older, a group of white lions, calling themselves the Outsiders, threaten their world. Led by the cruel Kiros (Mads Mikkelsen), these felines yearn for bloody vengeance and wiping out any potential rival kings. Mufasa and Taka leave home to preserve the royal bloodline. While on their own, they encounter lioness Sarabi (Tiffany Boone) and eccentric mandrill Rafiki (played in his younger form by Kagiso Lediga). This unlikely gaggle of animals sets out to find the promised land known as Milele…all while Kiros is hot on their trail and Taka begins to let darkness consume his soul.

Mufasa: The Lion King is a movie where everyone operates at 20%. That’s no reflection of individuals like the animators or actors being “lazy” or “bad.” It’s that Mufasa's artists must dial back their greatest creative impulses to fit into such a tediously subdued world. Great filmmakers like Satoshi Kon, Wes Anderson, René Laloux, Tomm Moore, and countless others utilized fully animated worlds to realize unbelievably unique character designs, sets, and images. Mufasa: The Lion King, like its predecessor, opts to just mimic reality. Anthropomorphizing is minimized. Backdrops are often merely dusty barren canyons or generic snowy mountaintops. With no room for imaginative flourishes, everyone from Jenkins to the animators is forced to stay in an unvarying style.

Take Kelvin Harrison Jr. as Taka/Scar, for example. Anyone who saw him in Luce knows this performer can deliver fascinatingly ambiguous and quietly eerie work. In playing a lion that gradually transforms from happy to brother to foe, Harrison Jr.‘s personality is dialed way down. His vocal performance lacks specifics because Taka can’t get too outlandish or oversized. That’s not how real lions behave. Thus, a talented performer is tasked with merely hitting very generic line deliveries. I guess this is all my fault for making a wish on that magical rock in 2019 that Harrison Jr. and Jenkins would work together…

A similar dearth of personality plagues the other voice-over performers while a sense of obligation permeates the script. Jeff Nathanson’s writing excels best in early scenes especially removed from familiar Lion King lore. Most creative is having Mufasa’s adopted tribe adhere to actual gender divides in lion tribes. The women do the hunting and the men? They just lounge around. It's also fascinating whenever his script (intentionally or not) intersects with recurring motifs in Jenkins' larger career. Specifically, there's the way Mufasa utilizes water. This form of matter often symbolizes birth and rebirth in art. Jenkins carries the torch of directors like Kenji Mizoguchi in translating that thematic symbolism into cinema.

Works like Moonlight (in Chiron's fateful trip to the beach with Juan) or Beale Street (in a bathtub birthing scene) featured water-dominated surroundings where life bursts through. In Mufasa, that fascination continues. A flood carries Mufasa to his new home while a deluge of water heavily informs the final showdown between good and evil. Meanwhile, Nathanson’s dreamlike digressions (the only welcome deviations from reality in the feature) to Mufasa imagining himself in a gigantic pool of water coated in heightened colors evokes previous Jenkins sequences like a blue-drenched vision of young Chiron standing in front of that important beach.

As the runtime plods on, though, these better screenwriting virtues vanish. Part of the issue is Nathanson becoming too fixated on providing answers to pre-existing personality traits and props. Rafiki's staff gets an origin story. Foreshadowing to Mufasa's ultimate demise appears twice. We even see how Pride Rock was formed! It’s perversely fascinating that the most expensive modern Hollywood productions are pastiches of the 1972 Rankin-Bass Christmas special Santa Claus is Coming to Town…and a poor pastiche at that! Any unique aesthetics or compelling drama suffocates under obligations to remind people of a 1994 movie. Also, Nathanson’s script is too crowded for its own good. The Mufasa/Taka relationship gets lost for a lot of the second act, with the latter character frequently vanishing into the background.

Recurring “modern-day” comedic beats with Timon (Billy Eichner) and Pumbaa (Seth Rogen) are incredibly unnecessary. Constantly cutting back and forth between the darker Mufasa/Taka storyline and these “wacky” antics encapsulates Nathanson’s inability to leave the familiar behind. Constantly cutting back to these recognizable comic sidekicks dilutes any dramatic momentum in Rafiki’s story. Returning to that animation style once again, the character designs further diminish any artistry in Mufasa. All the lionesses especially look the same, it's impossible to tell them apart! Blossoming love between Mufasa and Sarabi is hard to take seriously when I couldn’t pick one-half of the duo out of a crowd if my life depended on it.

Even Lin Manuel-Miranda’s songs lack the extra creativity he so effortlessly brought to Moana and Encanto's soundtracks. In 2019, Emily St. James of Vox wrote an excellent piece dissecting why rigid “realistic” computer animation and bouncy Lion King songs aren’t a good mix. Her grievances also apply here, even with occasionally stylized touches in songs like "Milele." The big early song "I Always Wanted a Brother" is an unquestionable bop, but the rest of the tunes lack much in the way of fun blocking or lyrics. A villainous ditty for Kiros is especially a miss simply because naming a tune "Bye Bye" in a film this serious is the wrong kind of incongruous. These musical numbers also awkwardly vanish for the entire third act. There's another instance of Mufasa: The Lion King’s lacking artistic commitment.

Hollow is the best way to describe the fourth Barry Jenkins directorial effort. That’s never a word I would’ve imagined using to ascertain his prior works dripping with vividly distinctive production design, powerful emotions, and uber-precise camerawork. Mufasa: The Lion King, though, has Jenkins constrained by the realistic visual aesthetic of 2019’s Lion King. In emulating reality, Mufasa fails to conjure up compelling fictional drama. What’s the point of new frontiers in visual effects if they only constrain artists? Everyone involved in Mufasa is capable of so much more. Their work here, though, lacks life and fails to move anyone at all.