Robert Zemeckis directed two of the best American movies of all time (Back to the Future and Who Framed Roger Rabbit). He's also spent the last decade on creative autopilot. As the band FLETCHER would say, "Two things can be true." Since the mid-2010s, Zemeckis has largely focused on narrative remakes of vastly superior documentaries (The Walk, Welcome to Marwen) or family movie remakes (The Witches, Pinocchio). Rehashing the past has become his modus operandi, including in a lengthy insufferable Marwen sequence involving a homemade toy time-traveling DeLorean.

Here, then, is a bit of a breath of fresh air. An adaptation of Richard McGuire's 1989 graphic novel of the same name, Zemeckis and screenwriter Eric Roth aren't rehash material that's constantly graced the silver screen before. Nor at they indulging in visual impulses any studio executive would demand. Unfortunately, the reunited Forrest Gump cast and crew can’t quite realize Here’s most audacious potential. Zemeckis is in a more ambitious mode here, but he still can’t get rid of his worst impulses.

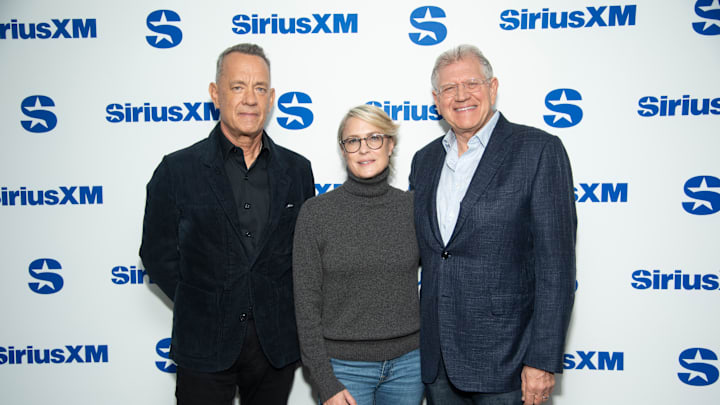

Here is told through an unmoving camera that's fixated on one spot in North America. Roth and Zemeckis non-linearly take viewers through centuries of existence in the house, including from the age of the dinosaurs to William Franklin's era to the eventual construction of a house in the 19th century. Many homeowners walk through the walls of this domicile, including an inventor responsible for the La-Z-Boy recline. Primarily, though, Here concerns the saga of the Young family. Al (Paul Bettany) and Rose Young (Kelly Reilly) moved into this place in 1945 after World War II and have three children here. In that brood is Richard (Tom Hanks).

This son falls in love with Margaret (Robin Wright) and the two raise a family here. Margaret quickly wants nothing more than to leave this home and realize some of her greatest ambitions. However, Here chronicles the hardship constantly befalling the Young family and other denizens of this house. If there’s one theme uniting Here’s various storylines, it’s tragedy. Whether you’re an unnamed Indigenous couple, a 1910s lady married to an early pilot, or a family dealing with the fallout of COVID-19, you cannot evade death and loss. Everything is finite. Nothing lasts. Time slips between all our fingertips no matter where we reside in the social hierarchy.

If nothing else, Here fully committing to that grim and melancholy atmosphere is commendable. Now in his 70s, Zemeckis is in a more retrospective mode than he was 30 years ago making Forrest Gump. The past is no longer a thing to romanticize to make Baby Boomers happy. Through Here’s deeply objective and non-sensational camera, yesteryear comes across as jagged, uncomfortable, and riddled with unrealized potential. In their strongest moments, performers like Reilly and Hanks do fine work communicating the toll of existence.

The problem with Here, though, is that its visual and thematic ambitions require a more delicate touch. For one thing, Roth and Zemeckis can’t stop writing dialogue that’s too cheeky and clever rather than observational and mundane. Every time viewers pop into the lives of characters, they’re delivering either “profound” ruminations on the existence or eventually outdated lines (“in ten years, nobody will ever remember the name Benjamin Franklin!”) meant to make audiences titter with knowing glee. Other pieces of dialogue (like teenager Vanessa’s “I guess no aerobics tonight!”) are written and performed like an alien trying to conjure up a vision of how “normal” humans behave.

This writing style prevents Here’s endless slew of characters from coming alive as people. Everyone’s verbiage seems designed to explain things to viewers, not reinforce individual personalities. That epitomizes the greatest flaw holding this production back. There’s a ham-fisted hand-holding quality to Here that doesn’t work with a movie with a camerawork style reminiscent of Notes from Home. Just look at a key sequence where Margaret returns home from the store and discovers a loved one lying on the ground unconscious. It’s supposed to be a devastating sequence. However, it’s drastically undercut through Zemeckis depicting Margaret’s movements in slow motion.

These visual cues meant to reinforce to viewers the importance of this moment to Margaret. However, this dramatic flourish just creates an additional barrier between the audiences and this character. It’s also deeply superfluous in a sequence whose emotional urgency is already apparent. Alan Silvestri's score also unfortunately suffocates this sequence. This composer does some terrific work in Here, including in his compositions anchoring a lengthy dialogue-free prologue. However, too often his melodies hammer home emotional beats that should emerge through subtle acting.

Then again, such acting often isn’t possible through Zemeckis once again lathering his actors in digital de-aging work. Here’s deeply intimate scope just seals the deal on how this style of visual effects wizardry is often (unless Martin Scorsese is behind the camera) antithetical to good acting. Richard and Margaret's early life sees the duo realized as plastic dolls thanks to all this CG. There’s a moment where digitally de-aged Robin Wright is cradling a CG baby that looks especially ludicrous. Anytime characters come up close to the camera and let audiences linger on their creepily smooth digital faces, it’s hard not to stifle laughter.

Here's darkest ambitions require something subtler. Yet Zemeckis is operating in a mode not far removed from his underwhelming family movies. Everybody is talking in very didactic dialogue and so many sequences are drowning in digital effects work. These qualities didn’t help The Polar Express, Pinocchio, or The Witches. They certainly don’t aid Here. Even the performances suffer from an archness draining them of individual personality. Zsa Zsa Zemeckis, playing Richard and Margaret's daughter, never gets a chance to exude a personality beyond the typical cranky teenager. Paul Bettany, meanwhile, is absolutely terrible with his incredibly loud performance as Al Young. His over-the-top line deliveries and derivative portrayal of a tormented mid-20th century father epitomize Here's unfortunate generic impulses.

Despite all those faults, though, I couldn’t bring myself to dismiss Here. There are some affecting moments in here, many of them coming from Hanks and Wright cutting through all the VFX nonsense to deliver something tangibly human. Zemeckis and cinematographer Don Burgess also demonstrate welcome commitment to the unmoving camera conceit. Their visual scheme also includes a nod to the source material involving the use of square panels that signal transitions in time. Ang Lee’s Hulk is beaming, I'm sure, seeing those panels on the big screen!

There’s certainly more going on in Here compared to other 21st century Zemeckis movies. It’s all a mess with some really ill-advised dialogue and visual effects work. Yet there’s something quietly interesting about seeing so much star power and money being used on a production so grimly aware of life’s innately finite nature. Death comes for everyone and Zemeckis is using McGuire’s graphic novel to reinforce that truth. That’s not enough to make Here anywhere near as insightful as your typical Ryusuke Hamaguchi or Kirsten Johnson movie. But at least it’s not Welcome to Marwen 2.0.