CW: Discussions of genocide, sexual assault, violence, and other disturbing topics is ahead.

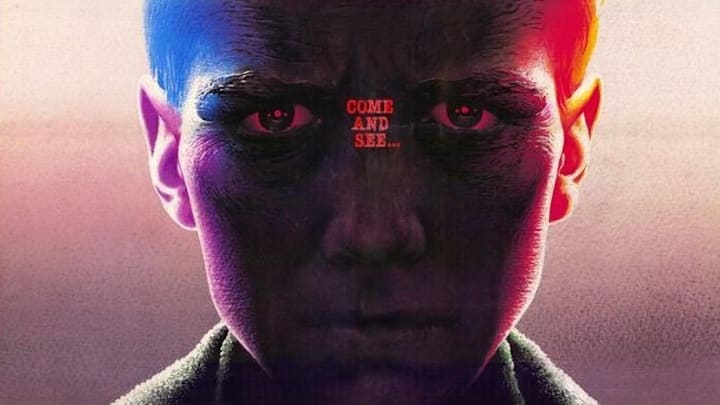

In American cinema, viewers are trained to look upward when explosions fill the screen. These fiery events make western audiences gaze to the heavens, seeing just how high the fireball has gone or bearing witness to how powerfully it’s spread shrapnel. Elem Klimov’s grueling masterpiece Come and See, though, ensured I’ll never look at an explosion the same way again. An early scene depicts Nazi bombers dropping explosives on Belarusian land firmly fixes viewers right on the ground as these devices destroy the grass and surrounding trees. Explosions are not a towering spectacle. They instead leave behind craters once teeming with life. All you have to do is look towards the ground to comprehend their full, desolate impact.

This is just the beginning of the grueling imagery writer/director Elem Klimov delivers. Klimov and co-screenwriter Ales Adamovich’s vision (drawn from pre-existing texts Khatyn and I Am from the Fiery Village) is a relentless, searing creation. Told through the eyes of young boy Flyora (Aleksei Kravchenko), audiences witness firsthand the horrors of Nazi's occupying Belarus during the 1940s. Klimov's choice for protagonist immediately differentiates Come and See from other motion pictures chronicling the anguish of genocide. Typically, such titles (especially when they hail from America), transpire from the point of view of outsiders discovering that these massacres are transpiring.

Schindler's List, The Killing Fields, The Zookeeper's Wife, these stories occur through the eyes of third parties or privileged societal members guiding audiences in discovering humanity’s most staggering horrors. Come and See, meanwhile, embraces grueling immediacy in representing atrocities on-screen. The camera is perched right inside crowds of people herded into sheds for slaughter, for instance, rather than offering viewers space between the lens and cruelty. Even the recurring motif of having characters stare directly into the camera reflects this emotional urgency. Klimov and cinematographer Aleksei Rodionov don't render audiences to a third-party distantly watching Flyora's unspeakable turmoil. We are in the same room as him. His mother pleads with us not to leave. Flyora's haunted, vacant eyes stare straight into the viewer's soul.

These visual qualities manifest in a narrative that begins with Flyora scavenging the beaches for a rifle from buried corpses. The way this youngster and his adolescent companion mock their deep-voiced elder and rifle through the sand briefly evokes childhood innocence. It won’t last. Before Come and See’s title card even comes up, Flyora and the viewer hear the thundering roar of a Nazi plane overhead. This feature’s excellent sound design makes this aircraft truly sound like a demon unleashed from Hell. Its rumbling engine makes your ears stand on edge, every noise it emits is so dissonant. Much like with the ominous drumming of IDF helicopters in Bye Bye Tiberias, these pealing roars on the Come and See soundtrack suggest the threat of constant apocalyptic doom.

How can one exist under such duress? As Klimov eventually shows, you don’t. Often, you just survive from one day to the next. Right after first experiencing these bombs firsthand, Flyora and fellow adolescent figure Glasha (Olga Mironova) wander through the woods seeped in madness. They romp in the rain, laugh uncontrollably, all while a crane follows the duo and unsettling music plays. It’s a nightmarish sequence rife with insanity that’s incredibly striking to see. This vivid depiction of Flyora and Glasha’s damaged psyches underscores the madness of a world where this violence is possible. How else to communicate this unspeakable status quo than through such trippy imagery divorced from reality?

Come and See’s imagery is incredible to witness, particularly when projected on the big screen showing I was able to experience thanks to the Texas Theatre’s Bleak Week programming. That 1.37:1 aspect ratio inspires so many incredible pieces of blocking, particularly any shots featuring as many as four separate layers of activity in one cramped frame. These visual tendencies are built on an underlying commitment to unblinkingly capturing genocidal horrors. It's a draining accomplishment to behold, but also one whose artistry is indisputable.

Countless films about genocide, such as Angelina Jolie’s woefully miscalculated In the Land of Blood and Honey, are full of brutality. Come and See, though, separates itself from that pack visually in several astonishing ways, including keeping many deaths off-screen. We see charred corpses and dismembered limbs left after landmines go off. However, families burning alive in farms suffer off-screen. Klimov briefly shows (in a wide shot) the aftermath of Flyora’s neighbors being slaughtered. However, we don’t see it happening in real-time. Even Nazi’s raping a woman is kept off-screen, though her tortured screams echo on the soundtrack. This is very much an attempt to remind people about the Nazi invasion of Belarus and the slaughtering of its people, which often get lost in history.

However, Come and See isn't necessarily about watching bullets enter people's skulls. It's about the screams of agony that will haunt Flyora for years to come. It's about the noises of suffering that powerful souls not only ignored, but lapped up like famished souls scarfing down dinner. This is a saga about how innocent civilians in war cannot exist or savor briefly joyous moments (like drinking milk for the first time in ages) because of all the rampant gunfire from unseen soldiers. As Come and See's final scene solidifies, this is also a story about how anyone can become a bloodthirsty monster. Even Adolf Hitler was once an innocent baby. Souls who support and normalize genocide can come from anywhere. The same is true of the origins of folks forever changed by the sight of violence. These and other narrative and visual priorities shape the precision and psychologically oriented informing what misery is on-screen in Come and See.

When we see anguish in the frame, it’s sequences like Flyora and Glasha nearly suffocating while trudging through a bog. These nightmarish set pieces (told with such skill in terms of camera positioning and the intentionally overwhelming score) end with the two characters surviving, which is its own kind of Hell. Come and See is about emphasizing the horror of innocent lives lost to Nazi scumbags. It also concerns, though, the psychological torment of existing in a world where that genocide exists. Flyroa bears witness to so much misery yet there is no death to promptly end his anguish. His suffering has just begun. That haunting reality lingers over everything.

The agonizing atmosphere also hinges on another specific element many films about genocide and militarized horrors forego: the spectacle of dehumanization and murder. The Nazi’s burning down villages and slaughtering civilians don’t mechanically carry out orders. They cackle with glee, shake their jowls, and clink drinks as they revel in screams of pain from their victims. It’s a sight evoking how white Americans would celebrate as they lynched Black men in the streets, or world leaders giving each other chintzy gifts over military-altered pagers that devastated civilian lives. Just this past week, reality TV stars were apparently working inside ICE raids to get footage for programs dehumanizing immigrants. The suffering of humanity is often a spectacle for the bourgeoisie to clap their hands in glee over.

Vividly portraying that disturbing facet of reality in Come and See is one of the many ways Klimov’s weaves his appropriately excruciating ambiance. This filmmaker refuses to look away from the souls responsible for historical atrocities, with unblinking extended shots and a cramped aspect ratio accentuating these horrifying sequences. Those overwhelming qualities are further enhanced through costume designer Eleonora Semyonova and production designer Viktor Petrov's contributions. Like the costumes and sets in The VVitch and A Hidden Life, Semyonova and Petrov’s accomplishments make viewers feel like they’re watching a lived-in reality from a bygone era. Those crumbling shacks Flyora and other characters live in are especially well-realized in their dilapidated conditions.

Come and See is a nightmare. It’s a rare film, along with select company like Lost Highway, unnervingly accurate in mimicking the powerlessness and ceaseless torment of the worst nighttime experiences. Ironically, tapping into that aesthetic lets Come and See tap into tangible wartime reality. The extreme misery and anguish of these historical horrors cannot be communicated through standard cinematic terms. They require a bold, relentless, and harrowing approach to filmmaking. That’s just what Elem Klimov accomplished with his final directorial effort. Hell is here on Earth. Come

(Sidenote: I viewed Come and See on the big screen at the Texas Theatre as part of the location's Bleak Week programming, it looked outstanding in a theatrical environment.)