CHAPTER 1

ESSIE

NEW YORK CITY

March 9, 1928

You could see her in the crowd, the lone figure walking at a fast clip down Lenox Avenue like she had the devil at her heels. She was in search of a taxi that could take her to Penn Station. She had no suitcase, just the clothes on her back and one painting in her arms—the last she would ever paint.

Gales coming off the Hudson River shoved at her like the rude pedestrians she passed along the way. Mostly boozehounds drunk on bathtub gin or giddy couples headed toward the drumbeats and the twinkling marquee of the Savoy Ballroom. She gave up trying to keep the panels of her mink coat close. Each gust of wind revealed a glimpse of the billowing silk nightgown she wore underneath, but thankfully, not the russet-red splatter.

“Hopped outta bed and didn’t even grab your clothes, huh, Sugar? Was he that bad?” one catcaller had shouted to her from the front stoop of a row house as she walked by, making his companions cackle and slap their knees.

Her teeth were chattering. Her feet, which were clad in damp men’s, white buck oxfords, were going numb. She longed to stop at one of the cabarets where jazz and ragtime music seeped through the doorways like cigarette smoke. She longed for just about anyplace that wasn’t wet with melting snow or cold, where she could sit for a minute or two, but she didn’t dare stop.

They’d probably discovered she was gone by now. They’d be coming after her.

Essie squinted, peering into the headlights of the passing cars. Among the Fords, Falcons, Packards, and Studebakers, she searched frantically for a flash of yellow. Finally, she spotted a taxi in the dis- tance, coming toward her. She ran to meet it, watching as the driver approached the curb. She waved him down.

“Stop! I need to get to Penn Station! Please stop!” she yelled.

But he didn’t. Whether it was because of her wild eyes, odd appearance, or her brown skin, she didn’t know. But the taxi driver kept going, though they’d locked eyes through the taxi’s glass. He continued down Lenox Avenue, his rear steel bumper receding into the night.

Essie dropped her hand.

“You need a ride to Penn Station?” a raspy voice called behind her. She whipped around to find an old Negro man staring at her. His hands were shoved into the pockets of a wool jacket. A cigar was clenched between his yellow teeth. She watched as he adjusted the bill of his flat cap then gestured to the beat-up Ford Model T where

he currently had one foot braced on the running board.

She nodded. “Y-y-yes.”

“I can take ya’ there,” he said.

“You’re a taxi driver?” Essie asked with disbelief, spotting no identification number on his vehicle or even a sign in the window that said he had a chauffeur’s license.

“Sure am!” He tossed his cigar to the ground and walked to the car’s rear door. He pried it open with a loud squeak. “Hop on in.”

She hesitated.

She did need a ride, and she knew that not all taxi drivers in New York, especially the ones that ferried Negro passengers, drove the yellow cars that traversed the city. But she had also lived in Harlem long enough to know that not everyone was who they claimed to be. What if she had just escaped one hell and was running toward another?

The man cocked an eyebrow. “You comin’ or not, honey?”

Essie started to walk away, shaking her head, but stopped short when she spotted another car at the end of the block, turning onto the street. Her heartbeat quickened when she saw the familiar sparkling grille and the white front fenders and hood. She began to tremble as the Rolls- Royce Phantom’s emblem came into view. The Spirit of Ecstacy sailed ominously toward her with arms outstretched, as if riding on the wind. She ran toward the Model T before tossing the painting onto the backseat and climbing inside. She grabbed the handle and slammed the door shut, catching the man by surprise. “Go!” she shouted.

His easy smile disappeared.

“Go!” she shouted again. “We need to go now!”

He didn’t ask any questions—to her great relief. He ran to the driver’s side and climbed behind the wheel instead. They pulled off seconds later.

When they reached the intersection, Essie eased aside the rear flap and looked to see if the Rolls-Royce was following them, but true to its namesake, the car had disappeared like a phantom.

Had it really been there? she wondered as the taxi drove toward Midtown.

“You runnin’ from somebody, sweetheart?” the driver asked, making her whip her gaze away from the rear flap to look at him. She stared at the back of his bald head, at the two rolls of fat over his shirt collar and his wide shoulders. “Your poppa comin’ after you? Or maybe one of them card sharks? You owe somebody some money?”

“No,” she answered softly.

The car fell silent as he waited for her to elaborate, but he would have to wait forever. How could she possibly explain to him—a total stranger—what had happened to her and not sound stark rav- ing mad? She was still grappling with what had happened herself, second-guessing everything even now.

But the splatters on her gown were a reminder, along with her painting—and the other token she now carried.

“This is the closest I can get you,” the driver suddenly announced several minutes later. He pulled to a stop along the curb and pointed to the granite building at the end of the block. “It ain’t that much of a walk, though.”

She swallowed, following the path of his finger. Penn Station may as well have been twenty miles away.

Essie dug into her coat pocket, pulled out a wad of crumpled dollar bills, and handed the driver his fare.

“Hey, thanks for the tip!” he shouted to her as she grabbed her things and leaped out of the taxi.

She walked swiftly to the entrance, keeping her eyes forward and stride long. But she could sense that she was being followed as she made her way to the main entrance. She stole a glance behind her.

Could she see white?

She turned her head completely and saw the Rolls-Royce Phan- tom again, gliding in her direction.

It’s not real, she told herself. It’s not real.

But it seemed real. She couldn’t help but run, nearly bumping into an older white man as she made her way into the station.

“Watch it, jig!” he shouted after her.

She ignored the insult and zigzagged her way through the crowd.

Essie was nearly out of breath when she approached the line in front of one of the ticket booths.

She’d done it. Despite the odds, she’d made it this far. All she needed to do now was to buy a ticket and board a train that would take her out of New York. But where should she go?

She could go back to South Carolina, back to her family. She could grovel at Aunt Idalene’s feet and ask her for sanctuary. But Essie wasn’t eager to do that or return to the old homestead with its tobacco barns and dirt roads, to the land of Jim Crow. Back home, she’d had to endure a lot worse than white cab drivers ignoring her and being called a “jiggaboo.” She couldn’t see herself settling there again, not after living up here in Harlem.

Besides, they knew where she was from. They could easily find her down there.

Maybe she could take a train to Boston or Chicago. Change her name. She could disappear in another big city.

“Next!” the woman behind the gated ticket counter barked. Essie stepped forward. “I . . . I need to buy a ticket.”

The woman rolled her eyes. Her pouty mouth, painted to look like Clara Bow, puckered with distaste. “Yeah, it’s a ticket window. You wanna buy a ticket to where?”

Essie hesitated, still unsure. She looked up at the departure board overhead. The train to Boston was exiting from Terminal 13. Thir- teen. That was a bad sign, and she had ignored the signs before—to her own folly. But the train number for Chicago was 26668. That wouldn’t do either.

“Hey!” the woman behind the counter snapped. “We’ve got other people in line. Either buy a ticket or—”

“Philadelphia,” Essie blurted out. “I want to buy a ticket to Phil- adelphia. Broad Street Station, please.”

The train to Philly was departing from Terminal 7. Lucky num- ber seven. And Louise was in Philly.

They’d both left South Carolina to follow their dreams. Essie would become a painter and study in New York. Meanwhile, Lou-ise would travel from city to city like a vagabond, taking jobs as a maid, a salesclerk, and even a nightclub coat check girl before finally settling in Philly five months ago, securing a spot as a hotel cleaner.

Louise wouldn’t turn her away; Louise would help. “That’ll be $2.60,” the woman behind the counter said.

While Essie sat in the waiting area, surrounded by people eating popcorn and peanuts, reading issues of the New York Herald Tribune and Photoplay, she knew that she was being watched.

They were watching and biding their time. They were laughing at her hubris.

She would never get away. Someone or something would stop her.

It’ll happen now, she thought as she walked down the platform to board her train, taking cautious glances over her shoulder.

As Essie listened to the “all boarding” last call minutes later and then felt the train lurch forward as it pulled away from the station, she had a death grip on the armrests, still anticipating some force stopping her or the train. Maybe a massive snowstorm. Or a derailment. Maybe the ground would open and swallow her whole. But as the skyscrapers and lights of New York City gradually disappeared from her window view—nothing happened. The train continued into the night. She loosened her hold on the seat’s wooden arms. She was both shocked and relieved that she’d regained her freedom. She’d escaped.

Essie realized this would probably be the last time she would ever see New York. She couldn’t come back. She said a silent goodbye to her art studio, to Central Park, to the jazz clubs she’d frequented, to the rent parties where she’d danced the night away, to the lovers she’d had, and to the friends she’d made.

The fatigue that had been tugging at her for hours finally won out. With her painting resting safely on her knees, her eyes slowly drifted close. Essie moaned and whimpered as she slumbered though, making one of the Pullman porters stare down at her worriedly when he passed by. He wondered what she was dreaming about.

Blood. A face contorted in pain. Being chased in the dark.

By the time Essie woke up, her train would be ninety miles out of New York City, only minutes from Broad Street Station. Back on the Upper East Side, a housemaid would find Maude Bachmann— esteemed philanthropist and Essie’s art patron—tangled in the bloody sheets on her four-poster bed.

The old woman’s eyes would be open and she would be stabbed three times—a mystical number—twice in the chest, once in the stomach.

The maid would let out a scream that would wake the entire household, maybe even the dead.

CHAPTER 2

SHANICE

WASHINGTON DC

PRESENT DAY

The painting has been hanging on the wall of my grand- mother’s bedroom for as long as I can remember. I call it The Portrait of the Defiant Woman, though I don’t think it has a name. I don’t even know who painted it.

The color palette is dark. Lots of browns, grays, and blues. The woman in the portrait—ochre-skinned with short, curly hair—is cradling a bundle protectively against her chest, covering her naked torso. The bundle’s fabric is made of intricate woven patterns. You can’t tell what’s in it; it could be bread or even clothes.

Her garb is a crude imitation of tribal. A crown of chicken feath- ers sits askew on her head. A necklace made of bones dons her neck. Probably not something someone from any real African tribe would wear, but the movie version circa 1940s Tarzan—a caricature of what tribal would be. But her face . . . her expression keeps the viewer from even thinking about laughing.

Her brown eyes are wide like she’s been startled. Her face, which is partially hidden in the shadows, seems to dare the viewer to look at her.

The portrait vaguely reminds me of Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, but more intense. It used to scare me when I was little. I always felt like the woman’s eyes followed me around the room, so I would avoid going in there.

Gotta clear out the house, Gram’s text says. That old painting is yours if you want it.

I squint down at my cell screen, surprised that Gram is giving away something she’s owned for so long.

Thanks, Gram, I type back quickly, not having time to ask her why she has to “clear out the house,” let alone why she’s giving up such a prized possession, because I’m too preoccupied with some- thing more important at the moment.

Jason is leaving me.

For the past few months, I could see it coming, like one of the many signs and omens Gram always talks about.

“Your hand itchin’?” she asked me once as I absently scratched my palm. “Looks to me like some lucky girl is about to get some money!” she said in a singsong voice.

Or when I was ten, my allergies were so bad that I got a sinus infection, and I made the mistake of complaining in front of her that I had an earache.

“Ears ringin’, huh?” Gram slowly shook her head and made a tsk, tsk sound. “Somebody must be talkin’ about you.”

I know I’ve inherited her superstitious nature because, like I said, I could see the breakup coming. The beard shavings left in the bathroom sink. The overflowing trash cans in our apartment. The nearly empty containers of ice cream and OJ I kept discovering in the fridge no matter how many times I threw the old ones away. They were signs of disrepair. Atrophy. Our relationship was slowly grinding to a halt like an old car engine.

And then, about a week ago, I returned home to find a stray cat asleep on our welcome mat. The black feline was curled into a ball with its eyes closed and its left ear flicking as it slept. It didn’t stir until I was nearly two feet away. When I came close, it jumped to its feet with its back arched and tail puffy, like it was going to defend its new home or die trying, but then the cat seemed to think better of it and scampered off, disappearing down the corridor.

The next morning Jason told me we were done. Today, he is making it official.

I drop my cell into my purse and walk out of our kitchen to head to work after loitering and avoiding having to say goodbye to Jason all morning. I grab my keys and my thermal coffee mug from the counter and watch Jason close the lid of one of the many boxes he’s amassed over the last week to move out of our apartment.

There are little cardboard mountains in every room now, and archipelagoes of garbage bags along the walls. They’re filled with items he plans to throw away or donate to the Salvation Army. I watch as he leans down to grab packing tape from one of the end tables to seal the box he’s just finished packing.

“I don’t understand why you have to do all this now,” I say, ges- turing to the box.

Jason yanks a long wad of tape from the roll with a piercing screech, making me wince.

“Why can’t you wait until I get home from work?” I ask over the noise.

I’m drumming my nails on the side of my mug as I talk. It’s a nervous tick and it’s annoying but I can’t stop.

“Why do you have to be moved out before then?”

I don’t think I can bear to come home to a dark, silent apart- ment. I imagine that all the boxes and our living room furniture will be gone save for a lone coffee table where Jason will leave his house key.

“Because the moving guys will be here in a couple of hours and who knows when you’ll get home anyway. You’re always working late.” He glances over his shoulder at me as he tapes the lid close. “Besides, what’s the point of me being here? What more is there to say?”

“What more is there to say? We were together for almost five years. You can’t give me a decent goodbye? You at least owe me that.”

Click, click, click, click. My nails drum to a steady beat.

I think about the early days and how much Jason pursued me. How he’d just happen to show up at our office building whenever I did every morning, or how we’d always end up at the same sand- wich shops for lunch, standing in line only a few people apart.

I found out later that Jason had been stalking me for almost a month before he finally asked me out, trying to work up the nerve to talk to me. And our first date had been so over the top—a private rooftop dinner and a Ferris wheel ride overlooking the National Harbor.

Where had all that fervor gone? Shouldn’t our ending match the beginning?

I want sobbing. Shouting. Maybe even some dishes to be thrown. Something melodramatic. Not this sad, unexceptional exit like two college roommates going their separate ways at the end of the semester.

Jason tosses aside the roll of tape. He turns away from the card- board box to finally look at me. I hoped to find his expression apologetic. Maybe he’s ashamed of how he’s treating me. Treating us. Instead, his nutmeg-hued face remains impassive. His dark eyes are flat.

“I don’t know what else you think I owe you at this point, Shan- ice. Considering how much I’ve been carrying the weight of our relationship . . . hell, carrying you for the past year, I don’t really feel like I owe you a thing.”

I stop drumming my nails. I’m shocked into silence.

It wasn’t a shout or a dinner plate hurled at my head, but it hurts just as much.

“Fuck you,” I say because I can’t think of anything else.

I walk to our apartment door. My hand is shaking as I grab the doorknob and slam the door shut behind me.

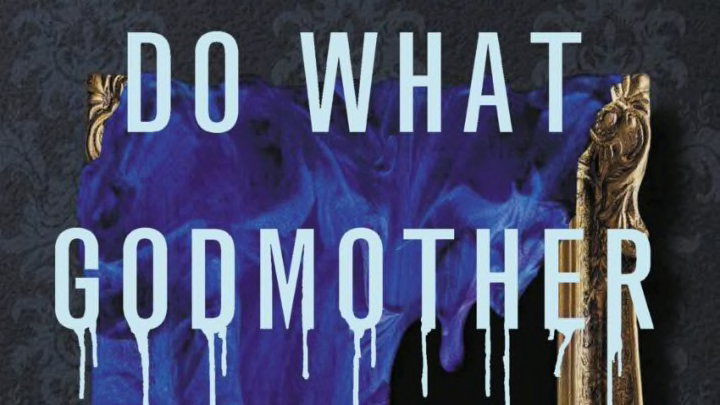

Do What Godmother Says by L.S. Stratton is set for release on June 11th, 2024.

If that excerpt is enough to get you excited, then don’t forget that you can preorder Do What Godmother Says now. You can also find the full description and the author’s bio at the preorder link as well. Honestly if those two chapters weren’t enough to get you excited, then I don’t know what else will.

What do you think of the cover and teaser for Do What Godmother Says? Let us know if you’re adding it to your 2024 TBR!