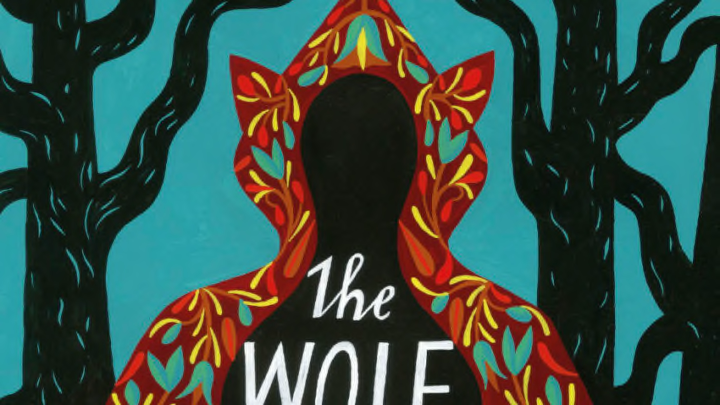

Ava Reid’s debut novel The Wolf and the Woodsman is a fantasy story with beats that feel familiar – an outcast young woman shunned by her people for not possessing magic, taken from her village by a group of men who want to harm her simply for being other, who finds an unexpected connection with someone she had always considered her mortal enemy.

Yet, the beauty of Reid’s story is that she manages to take these familiar pieces and forge them into something that nevertheless feels as though we’ve never seen it before. A richly imagined exploration of faith and folklore that doesn’t shy away from the dark side of the way both are often weaponized against those with the least power, The Wolf and the Woodsman is lushly written and thoroughly evocative – whether it’s the specific coldness of brutal winter landscapes or the sudden and often violent deaths that befall those simply trying to survive.

The story centers on Evike, a young “wolf-girl” from the village of Keszi, who is the only girl living in her matriarchal society who was born without the magic the other women share. She has grown up shamed and bullied by her peers for this “otherness,” even as their village is deemed pagan and persecuted by the king and his Holy Order of Woodsmen for their polytheistic faith.

The King, who follows a monotheistic religion called the Patrifaith, takes a girl from Evike’s village every few years in a sort of twisted blood tribute that allows the rest of them to survive mostly unmolested in the between times. But when the Woodsmen arrive in her twenty-fifth year demanding they be given a seer with the power to have visions, her village elder is willing to send Evike to die instead of someone with the rare gift to foretell dangerous storms and potential famines.

But when the Woodsmen assigned to take her back to the capital are set upon by monsters, almost all are killed, save Evike herself and the group’s captain, who is secretly Prince Bárány Gáspár, heir to the throne. Gaspar’s father, the king, is desperately seeking a magical advantage to the war that has been raging for years, and the prince himself is battling to suppress the growing faction of citizens who support his despotic half-brother who longs for the throne for himself – and a chance to cleanse all those he deems insufficiently pure from their lands.

As the two uncomfortably join forces to try to prevent an outcome that would harm both those who practice the Patrifaith and those who do not, their quest will cause Gaspar and Evike to reevaluate everything they’ve ever believed – about Woodsmen, about wolf-girls, and about faith itself.

Evike makes for a compelling heroine, full of resentment at years of slights and torn between the two halves of her heritage. Half pagan and half Yehuli (this novel’s lightly fantasized version of Judaism), her struggles to make a place for herself in a world where the smallest differences are weilded like weapons are fascinating to watch. In all honesty, her trips to visit her long-lost father’s Yehuli community, where she learns a new language and faith tradition, make for much more compelling reading than some of the more repetitive segments in which Evike and Gaspar repeatedly recognize, reject, and occasionally give in to their growing attraction to one another.

But what really makes The Wolf and the Woodsman remarkable is the deft way that Reid writes about the various faiths at the center of the story – from the strangely similar myths that tackle familiar themes, to the ways each relates to power and prayer, there’s much to dig into and think about here, from issues of identity and acceptance to religious persecution and mythmaking.

All in all, a satisfying tale that has left me eager to see what this author does next.

The Wolf and the Woodsman is available now. Let us know if you plan to give it a look.