Alex Garland’s Men, though home to some gruesome body horror effects, is a meandering, self-important approach to allegorical horror that misses its metaphorical mark.

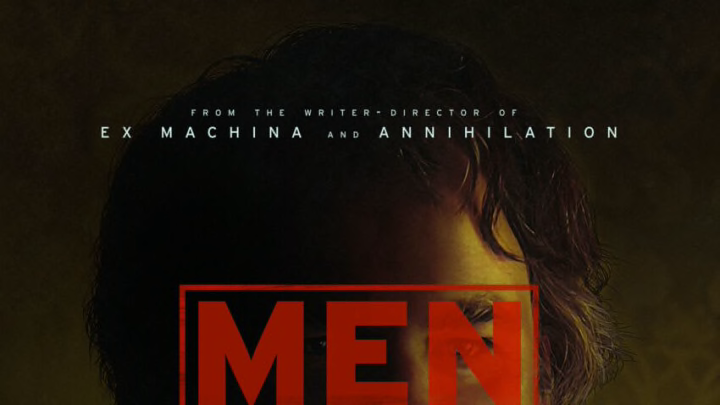

Between Midsommar, X, Hereditary, The Lighthouse, and Lamb, A24 has more than cemented itself as the go-to studio for strange, genre-bending horror flicks, and their latest collaboration with Alex Garland, Men, is no exception. Revered for his previous success with surreal thrillers Ex Machina and Annihilation, the promise of Men – an eerie slow-burn horror about trauma and misogyny – seemed like another surefire hit for both Garland and A24. Tragically, Men is a notable misstep in A24’s horror hot streak – a self-important approach to feminist horror that (though boasting some truly gruesome effects) falls short of meaningful commentary and spine-tingling horror.

Starring Jessie Buckley and Rory Kinnear, Men follows Harper (Buckley), a traumatized young woman who takes a trip to the quaint English countryside to get a fresh start after the suicide of her abusive husband, James (Paapa Essiedu). Though, at first the secluded cottage in a sleepy town seems like the perfect escape for the haunted Harper, she quickly becomes the victim of a stalker (Kinnear) after an unsettling encounter in the woods. As the village townspeople slowly morph from harmless to menacing, Harper struggles to cope with her unacknowledged trauma – and escape the night with her life.

It must be acknowledged that – for all of Men‘s failures – not a single ill word can be said about neither Buckley nor Kinnear, both of whom turn in outstanding performances that give the film its few moments of genuine terror and brilliance. Of course, Jessie Buckley’s Harper is the beating heart of the film. It should come as no shock that Buckley delivers yet another grade-A performance, but she’s able to help bring warmth and relatability to Harper’s bare-bones character.

It’s frustrating to see a film so intent on proving itself feminist give its female protagonist so little to do. Still, Harper is a walking stereotype and singularly defined by the trauma inflicted on her by the men in her life. Though she does have moments of resistance and strength, she spends most of the film on the defensive – never truly able to take control of her narrative or even find vindication for her traumatic past. The sheer lack of character depth could also be a byproduct of the deliberately unsettling, murky tone that permeates the entire film, but for Harper’s character to be sacrificed in the name of aesthetic and allegorical value is disheartening, to say the least.

Still, even with the bare-bones material she’s given, Buckley more than pulls her weight – an impressive feat considering she has far and away the most screen time and is often the only character speaking in most scenes. That being said, though, Buckley’s performance wouldn’t be nearly as dynamic if she wasn’t playing off the jack-of-all-trades brilliance that is Rory Kinnear, who plays almost every inhabitant in the town with whom Harper interacts.

Though we struggle with the script’s attempted metaphorical message overall – especially in regards to how it positions Harper and her ex-husband, the decision to have a single actor play almost every other male character in the film is undoubtedly a brilliant one that adds a menacing air to the film – an ever-present awareness in both Harper and the audiences’ minds that it’s her against the rest of the world.

Among Kinnear’s arsenal of characters are a kindly homeowner, a mischievous schoolboy, and a leery priest – and though the writing overall doesn’t allow for much character exploration, Kinnear commits wholeheartedly to bringing as much depth and dimension to each individual persona as possible. While some men of the village – like the priest – are unquestionably villainous, there’s a strange empathy and relatability that Kinnear is able to invoke with a number of his performances that makes it difficult to root entirely against the multi-faced monsters, even if things do take a nasty turn in the final act.

Speaking of the film’s final act, the last half hour is the film’s most memorable – thanks in large part to a particularly gruesome, demented procession of bloody visuals that will make even those with the most iron-clad stomachs squirm. While the effects are certainly top-notch, and the pacing makes for a suitably scary finale (if the film’s only genuine foray into the horror genre), the metaphorical meaning behind the constant birth, death, and birth of the men chasing Harper feels underdeveloped and flimsy.

Men has the frustrating tendency to set up so many visual and narrative elements – the flashback and flash-forwards to Harper’s husband’s suicide, a number of religious images from varying backgrounds, and pagan birth rituals, to name a few – and then neglect to pay them off or resolve their placement in any meaningful way. Though the visuals will certainly cement a place for Men in horror history, and Rory Kinnear’s multi-role performance creates a singular dread that will stick with us, there just isn’t enough substance or tact put into Men to make it the allegorical folk horror masterpiece it could’ve been.