Joker is a self-serious movie that, in spite of its lead, posits itself as revolutionary when it never hovers above bland and tasteless.

There’s an inherent worry saying Joker is a bad movie, particularly with the knowledge that female writers have been threatened for stating just such an opinion. But it’s telling a telling statement, both from the angle of women being terrorized to readers being so riled up over a review that they would go to such lengths. Maybe that’s what happens when a movie so unabashedly strives to give justification to the Clown Prince of Evil’s actions as Todd Phillips’ Joker does.

Phillips wears his inspirations more proudly than Quentin Tarantino, but where Tarantino finds reverence in his source material and, more importantly, understands the tone of those inspirations, Phillips perverts and twists the meaning of all his homages, from Taxi Driver to Network. Slather on so much pretension masquerading as high art and you have an insufferable, two-hour snoozefest that should make you look askance at anyone who tries to justify their appreciation of it.

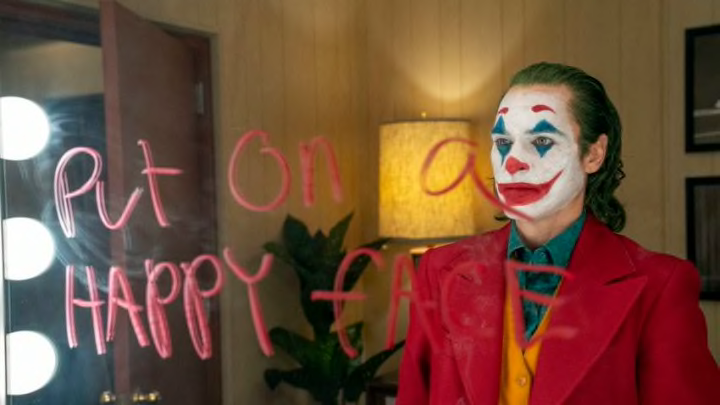

Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix) is a clown by day and a wannabe stand-up comedian at night. When he loses his job, it takes him down a path of darkness, complemented by the horrors of a ’70s-tinged Gotham City that’s already decrepit. Arthur will unleash his id, known as Joker, and spark a revolution from which there’s no return.

It’s impossible to separate Joker’s narrative from what director Phillips wants to gain with it. Set in the garbage strike world of 1970s New York (er, Gotham City), Arthur lives with his mother (Frances Conroy) in a pretty decent apartment considering the near chronic reminders that they’re struggling. It’s a world where people are so cruel that black and Latino children beat on Arthur just for kicks, leaving Arthur as the broken man whom no one believes, purely because his boss doesn’t like him. The only one to throw any kindness his way is a young single mother (played by Zazie Beetz with just slightly more lines than Margot Robbie’s Sharon Tate).

The problem is watching this in 2019, with Phillips acting to remind you that, apparently in 1976 this was actually OK. Arthur plays with a little boy only to be told off by the kid’s mother, yet the audience is meant to perceive this as an overreaction. A woman is harassed by three men on the subway and at one point looks to Arthur for kindness only to have him do nothing.

Is Arthur supposed to be a repressed hero beaten down by society? It’s unclear because the script doesn’t seem to understand what everyone’s problem is. When all else fails (which happens too much in this movie), Arthur falls on minutes of unhinged laughter.

These moments, which go on forever, are passed off as indicative of Arthur’s mental disability; he has a card he shows to people during his laughing jags. This is actually a real illness called, in layman’s terms, emotional incontinence, but there’s no belief anyone associated with the film knows of this.

Instead, his “disability” (in quotes because the third act leaves some questions about it) is utilized to explain away bad actions. His personality isn’t weird; he’s disabled. His actions aren’t bad; he’s disabled. This is contrasted with an actual disabled character, a little person who is routinely ridiculed by another friend of Arthur’s and, in one scene, is placed as a punchline because he can’t reach a lock. If this is what Phillips says he can’t joke about, he’s wrong, as my audience was howling (with me, the lone disabled critic, cringing).

There’s no doubt Phoenix commits to the character. His Arthur is creepy and off-putting, but it’s obvious Phoenix wants to infuse vulnerability and nuance into the character. When he first performs onstage there’s an earnestness to him. He wants to connect with people. But since the script is so content to have Phoenix dance around his underwear or laugh, it’s hard for Phoenix to really promote the character beyond that. It presents a disconnect between the actor’s intentions for the character and the directors.

With the film clocking in at two hours, this disconnect also extends to the plotline. Not much happens in this movie despite so much happening. There are several plot points that develop, but they ramp up heavily toward the third act, leaving the first 45 minutes or so as an aimless pastiche of ’70s features and mind-numbing sequences of Joker laughing, dancing, or otherwise just watching things in silence.

And when a character does talk, it’s in a somnambulant monotone, as if they’re being put to sleep on-camera. After the rough first hour, there are plots involving the Wayne family, Arthur’s background, and his interest in talk show host Murray Franklin (Robert De Niro) — which are interesting, but they’re all stopped dead by moments of Joker just… being weird. There’s not a sense of plot so much as a sense of discomfort, and that’s not enough to sustain 120 minutes.

When the violence does happen, it’s brutal, uncompromising, and way too authentic. Much has been written about what type of people a movie like Joker will attract, and it’s hard not to plainly see what the script thinks of Joker: He’s a deranged revolutionary failed by a crumbling government system. (Seriously, if Phillips wants to hear about the crumbling government system involving people with disabilities he should pull up a chair.) It’s hard watching Phoenix baldly chase down people and shoot them, or blow someone’s head off in long shot and not think of our times. Phillips wants you to, but it’s unclear what he hopes you’ll gain from it.

At the end of the day, Joker is just boring. That’s the cold truth. Joker believes it has such a new and unique message, that it’s a piece of art. But really it’s as tacky as a velvet painting. Phoenix is great, but he always is, and because no other character is really that defined this is pretty much a one-man show. If you must see it, make it a rental where you can pause and take a shower.