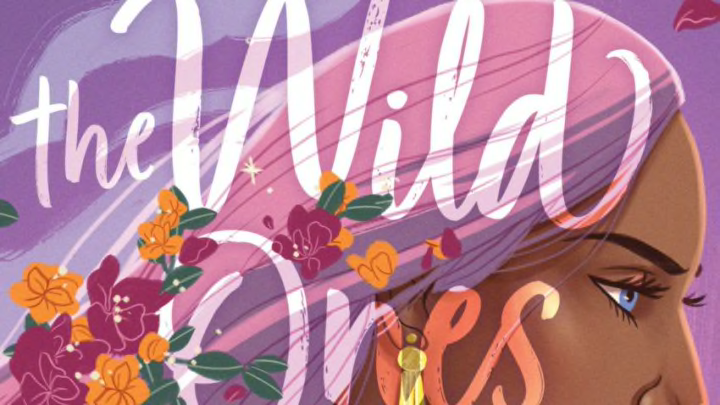

Exclusive: See the cover and read an excerpt from The Wild Ones by Nafiza Azad

By Lacy Baugher

Read an exclusive excerpt from The Wild Ones below.

"Once upon a midday marked by the blooms of pink and purple bougainvillea, she was born. They named her Paheli. A riddle. And she was. And she is. And may she always be. A few words of caution before Paheli tells us her story. We would have you know that the tale she weaves may be true or it may be a lie. Or it may be a khatta meetha, sweet and sour, mixture of both. We don’t know. What we do know is that every story has a beginning. And this is ours. The Beginning, or How Paheli Became the First Wild One; With a Cameo by Taraana, the Boy Made of Stars. I lived a life of spark and charm (false, of course) and (manufactured) wit and splendor. I lived my life on my toes, on a precipice, poised to fall. And fall I did. But let me begin at the beginning. My mother was a whore. Not a tawaif as she aspired to be, but a whore. Men visited my mother’s body as though it was a city they were supposed to conquer. I don’t know what circumstances led her to this profession, and she never volunteered the information. She named me Paheli because she said I was a mystery. Whether I was a result of a yearning or a moment of weakness, she wouldn’t say, and over time I learned not to ask. I know nothing of my father. No . . . that is not quite true. My eyes are the blue of Afghani skies like his must be. My skin is a deep brown like the earth after its first sip of rain. My mother’s skin is the color of day-old dough. We lived in the City of Nawabs in India. Now Lucknow, back then it was known as Awadh. It wasn’t just the city of nawabs, however; it was also the city of tawaifs. What my mother wasn’t but what she wanted to be so desperately. I remember the smells of the kotha. The first floor was rank with the smell of cheap perfume the first-floor whores applied liberally. The aroma of food emanating from the kitchens vied with the stench of the refuse that waited for attention right outside the back doors. Below all this was another scent, one that I now associate with despair. The second, third, and fourth floors of the kotha were the domain of the tawaifs. The air in those rooms was infused with fragrances created exclusively for them. What is a tawaif if not a whore? A tawaif, sisters, is a courtesan. She is well versed in the arts of conversation and seduction. She is schooled in music and dance, particularly the mujra. She sings ghazals and plays instruments. Her intellect is formidable and her beauty so divine that the moneyed nawabs paid fortunes to partake of it. Not for her a dingy, dark room in a row of dingy, dark rooms on the first floor at the back of the kotha. She has a scented boudoir, decorated in silk and satin. Men seek pleasure from her; they do not simply satiate their lusts. Grace, elegance, and choice: a tawaif has them all. I grew up learning to keep my eyes cast down lest I be the recipient of unsavory notice from my mother’s clients. I never left the kotha; I wasn’t allowed to. Girl children are tender morsels to those whose hunting grounds are the city’s pavements. There were other children in the kotha—some were even my friends—but our first loyalty was to our mothers, and our mothers were often embroiled in complicated feuds with each other. Though the kotha was always full of people, I sometimes went days without speaking to a single person. My mother’s face had been disfigured by a childhood illness, which made her dream of being a tawaif precisely that: a dream. Still, the sisterhood in the kotha was not exclusive, and the women would have enfolded her within its arms had my mother been a nicer person. She wasn’t, though. She wasn’t nice at all. So, she was reviled around the kotha, and the only reason the Malkin, the owner of the kotha, tolerated my mother was because she liked me. I grew up on scraps of attention thrown my way by the various whores on the first floor. The second, third, and fourth levels of the kotha were forbidden to us children unless we were sent on errands. My mother mostly kept me in that windowless room that served as home, apart from the time she worked. Those hours, from five in the afternoon to two in the morning, I was left to my own devices. When I was young, my mother paid a kitchen maid to take care of me, but after I turned five, I was deemed old enough to look after myself. What do I tell you of the evenings at the kotha, sisters? I used to slip under a table set on the side in the central courtyard and peek out from behind the overhanging tablecloth at the spectacles that unfolded there every evening. The evening gatherings, the mehfils, were filled with color; each tawaif was dressed in bejeweled finery, and glowing with life and laughter. The sweetness of the ghazals they sang enraptured me. I was too young to appreciate the sly wit in the banter the tawaifs and the nawabs shared; too young, at first, to understand the incomprehensible whispering between two hearts that people fancifully called romance. The nawabs who frequented the kotha were peacocks; knowing that their money alone wasn’t enough to attract attention, they seduced as much as they were seduced. I would fall asleep under the table and wake only when I could no longer hear the bells of the ghungroo the tawaifs wore to dance. The city outside the walls of the kotha was unknown to me and would remain so until the year I turned sixteen. My mother had been trying to get the Malkin to take me on as a tawaif-in-training but to no avail. My skin wasn’t fair enough, the Malkin said. I was fiercely glad. My mother’s ambitions for me aside, I had no plans on whoring myself. I didn’t know what I planned to do with my life, but I knew with a certainty that my mother’s trade was not for me. Not that my desires meant much to my mother. My blue eyes were a ticket she meant to use to elevate her status. So, she sent me, ostensibly on errands, to the tawaifs’ domain, hoping I would run into a nawab and gain his interest. But I subverted her commands at each point. If I couldn’t avoid being in the presence of the nawabs, I would wear my most mulish expression and keep my eyes cast down. Would you look at a dandelion in a field of orchids? They didn’t either. I only let my guard down once and only for half a second. I thought I was safe; I thought that no one was around. I should have been safe. It was early in the morning when the denizens of the kotha were all asleep. I had spent the night under a table again, though at sixteen I was a bit too large to properly fit under there. The courtyard was lit dimly by a few glass lamps scattered here and there. I walked, rubbing my eyes, not seeing where I was going, and kicked a ghungroo that had been lying on the floor. I picked it up and shook it, smiling at the sound it made. When did I realize I wasn’t alone? A sense of danger ran a shiver down my spine, and I looked up at the stairs that led to the second floor. A man, still wearing the effects of the sleepless night on his face and his clothes, stood there. His eyes met mine and widened in surprise. He smiled. Startled, I dropped the ghungroo and ran. I should have known to be afraid. Days passed and I made another unforgivable mistake. I forgot about the encounter in the dark; I forgot about the man. The Malkin told me about a tawaif who had retired and needed a girl to work in her home. I wanted to be that girl. I was full of dreams of escape. Perhaps my mother noticed. That day, sisters, dawned red. Not that the day has any business with the work of the whores, but nevertheless, the day dawned red. My mother was uncharacteristically kind that day. She told me it was my birthday, and as I didn’t know any better, I believed her. She fed me halwa puri, combed my hair, and embraced me for the first time in a long while. Later, she made me dress in a gharara she had borrowed from an acquaintance. Then, when the first stars of the night were dotting the horizon, she took me to a party on the rich side of the city. I should have questioned her then, but I didn’t. I should have known to be suspicious, but I was bedazzled by the attention she was giving me. So, I followed her to that party. She was my mother. I thought she would never do anything that would harm me. He was there, that man who had been on the stairs that morning in the kotha. The man about whom I had forgotten. He was there. You all have known a similar flavor of pain, sisters. Even if I don’t put it into words, you know what happens next. The same old tale of the lamb and the wolf. You have heard it before. You have lived it before. I escaped too late, running out of the nawab’s haveli on bare feet. I was bleeding from the gash on my arm, from the scratches on my face, from between my legs. It hurt to run, but it would have destroyed me to stay. The night was alive and the city streets blurred as I ran without direction, without thought, without reason. I ran and ran and ran and would have run further still had I not turned a corner and bumped into that boy. We both fell from the impact. His lips were split, and he coughed up a mouthful of blood. He looked as shattered as I felt. We stared at each other under the pale light of the half-moon. He had a five-pointed star in the pupil of each eye, and his skin glowed gold like he was made of stardust. My reality receded slightly when I looked at him glowing like a desert in the afternoon sun. The boy got to his feet and made to go. Then he stopped and turned back to me. Without warning he tossed me a box. I barely got my hands up in time to catch it. I blinked and he was gone. I was left with the night, left with the pain; left alone, scared, and shattered. My reality reasserted itself. At that moment, the shadows provided an illusion of safety, but where would I go next? I couldn’t go back to the kotha. I definitely wouldn’t go back to that woman who no longer deserved the title of my mother. I looked down at the box in my hands. It was plain brown wood. I opened it and took a deep breath. On a square piece of black silk was a collection of stars. The stars in the box were identical to the stars in the eyes of the boy I had bumped into. I picked one up and placed it on the palm of my hand. The sound of voices coming from behind me made me tense, and I clenched my hands into fists without realizing. The star dug into my hand, and all of a sudden, a fire flamed in my veins. I squeezed my eyes shut, intensely aware of my ravaged body, the road underneath my bare feet, my torn clothes, and the pain. Always the pain. The skin on my palm stung, and when I looked at it, I saw that the star I had been holding was now embedded there, like a badge or a medal. I looked up and the world was different. I managed to get to my feet, though my knees buckled once or twice. I put a hand, palm flat, against a wall for support. A door appeared in the wall I was touching. Golden light glimmered from underneath the door. I didn’t question it, sisters. I pulled the door open, and stepped through."

Mark your calendars – and let us know if The Wild Ones looks like it belongs on your TBR shelf!